There is no definitive test for Doose syndrome. Instead, it is diagnosed based on a cluster of clinical (types of seizures witnessed by parents and medical professionals), onset, and EEG (Diagnostic Test used by Neurologists) findings. There are seizures and EEG results that are hallmarks for this particular condition and differentiate it from others, though sometimes kids don’t seem to fit all of the categories for any syndrome exactly.

In about 60% of cases, Doose syndrome starts with febrile or afebrile generalized tonic-clonic convulsions. Alternating tonic-clonic and hemi-tonic-clonic seizures are a possible presentation. Some days or a few weeks later, myoclonic and/or myoclonic-atonic seizures appear in abundance, sometimes in combination with short absence seizures. This often begins to feel like a cascade of events with seizures coming on faster and faster and can be overwhelming for parents especially if they are not prepared for it.

Doose syndrome (Myoclonic-atonic Epilepsy) usually occurs in children with an uneventful history; there is likely to be no pre-existing neurological disorder and usually normal development before onset. Many parents have found that getting a baseline assessment of developmental milestones at the very beginning of onset can be helpful down the road. Because both the seizure activity and the types of pharmaceuticals often used to treat the condition, it is likely you will see some developmental regression.

Fortunately, there is hope that children can catch up once the seizure activity is eliminated or reduced, particularly with a later onset and gift of typical brain development, but this can take time. Doose syndrome is not a guarantee of long term intellectual disability, but it will take a holistic approach to maximize your child’s potential outcome.

In 94% of the cases, epilepsy starts within the first five years of life. Often this occurs between 2 and 3 but can range from as early as one month to five years. Other disorders such as Dravet Syndrome are more typical at younger ages.

In 100% of cases, the child develops myoclonic and/or myoclonic-atonic (or drop) seizures. The -atonic (loss of muscle tone) feature of the myoclonic-atonic seizure is rare and hallmark to Doose syndrome (MAE) and is the most important and distinct feature which helps differentiate it from other syndromes. Later in this section of the site, we will go into the seizure types with more depth. Also, descriptions of the seizure types can be found in our “Doose Dictionary” which you can find here.

In addition to myoclonic seizures, children may also have a combination of other generalized seizures including tonic-clonic, absence, and non-convulsive status epilepticus and, rarely, tonic seizures.

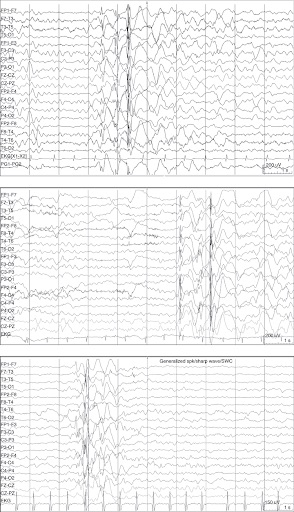

Hallmark features on an EEG (Diagnostic Test used by Neurologists) help define Doose syndrome and, in almost all cases, rhythmic parietally accentuated 4-7 Hz background seizure activity develops early in the course. (See Doose Dictionary under “Background Activity”)

Your neurologist or epileptologist will work to rule out similar conditions some of which are more severe, others less severe. (Differential Diagnosis) including Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome and Dravet Syndrome. While Doose syndrome is a severe childhood epilepsy syndrome, the potential for a positive long term prognosis is much more significant than children diagnosed with either of these conditions.

It has been said that if you are going to receive a catastrophic early childhood epilepsy diagnosis – Doose syndrome is the one to get. That is small comfort given the circumstances, but it does give us the charge to have hope and strive for seizure freedom and a somewhat “typical” life for our children. If seizure freedom cannot be fully realized, significant improvement in the quality of life and outcome can be found through various treatments.

A quick Aside about Working with Neurologists:

The nature of this disorder, its rarity, and its relation to several other disorders can make it difficult for neurologists to be certain of a diagnosis. This is a reason why you want to work with a physician who has experience with Doose syndrome and other childhood epilepsy syndromes. Typically these are specialists called epileptologists found at Epilepsy Centers.

You can find a list of these centers here.

Find An Epilepsy Center

Usually, these doctors are very good at making a diagnosis. However, many of us have had diagnoses that sound like “This is probably Doose syndrome,” or “This is almost certainly Doose.” Some of this comes from the nature of neurology and our limited knowledge of the brain. Some of it comes from neurologists reluctant to make an absolute diagnosis only to have things change dramatically and thus leave families angry or frustrated with them. We welcome everyone with Doose syndrome and variants, we have a lot to learn here.

What is important is that, for the most part, neurologists are doing the very best they can, and care deeply about helping your child. Some of them may have a bedside manner that may leave you wanting. In those cases, seeking a second opinion could always be an option, but it has been the experience of many of us that what we lose in bedside manner we often gain in brilliance.

In working with them know that it is a rare specialist in any field who is both extremely skilled at communicating well with patients and families and off the charts brilliant in a way that can help save your child. Just a word of warning to balance priorities as you assess the level of care you are receiving. One way to work through this is by connecting with other parents in our Facebook group and asking questions.